By Miriam B

Tiffany Cabán’s extraordinary grassroots campaign for Queens District Attorney is heading to court over the validity of 114 affidavit ballots. The manual recount of nearly 91,000 ballots ended Thursday, July 25—a full month after the primary election—with Melinda Katz ahead by about 60 votes. Here are some opinionated reflections on the campaign waged by Cabán, a queer Latina public defender and DSA member.

Win or lose, the Cabán campaign changed the conversation about mass incarceration. In endorsing Cabán, The New York Times wrote, “The success of any prosecutor, and of the city itself, depends on keeping people safe. Ms. Cabán is the Democrat best poised to become one of a growing number of prosecutors to show that can be done without infringing on civil liberties, criminalizing black and Hispanic Americans and mistaking punishment for the only form of justice.”

Over the course of the campaign, the other six candidates adopted many of Cabán’s positions, though none went as far in calling for an end to the-lock-‘em up culture in Queens that has disrupted hundreds of thousands of lives, mostly for black and brown people. Cabán’s campaign also prompted three U.S. Senators running for President—Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris—to discuss decriminalization of sex work.

Win or lose, Cabán’s campaign dealt a severe blow to the Queens County Democratic Organization, a.k.a. the machine. It is astonishing that Borough President Melinda Katz, the only candidate in a field of seven to have run—and won—countywide before, didn’t win a clear victory, when she had $2 million to spend and the endorsement of the machine and many labor unions. To be fair, Judge Greg Lasak’s strong vote count in more conservative neighborhoods was likely at Katz’s expense. If Lasak had dropped out—as Rory Lancman, another, more progressive candidate, did a week before the election—Katz would probably have won.

While Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez received no endorsements from elected officials in her primary campaign last year, Cabán received many. Elected officials in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx bucked the machine to endorse Cabán. Other endorsers included New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer; Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner; Suffolk County, Mass. DA Rachel Rollins; and US Senators and presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

Cabán also built a more robust coalition than Ocasio, in less than half the time. Many endorsing organizations were outgrowths of Bernie Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign or Ocasio’s campaign in 2018. There were also national criminal justice organizations (Real Justice and Color of Change) and organizations for former prisoners and the homeless (VOCAL NY Action), immigrant rights groups (Make the Road New York Action), LGBTIA groups (Jim Owles Club), and sex workers’ rights groups (Red Canary Song), as well as traditional neighborhood groups.

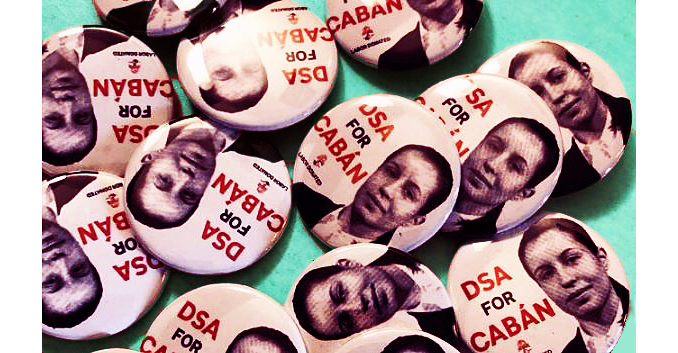

DSA played a central role. Aside from a few of Tiffany’s friends, most of the people who signed on early were DSA members. NYC-DSA was the first organization to endorse Cabán, and State Senator Julia Salazar, a DSA member, was the first elected official to endorse her. DSA members also played a key part in getting some other organizations to endorse, built the field operation, and provided well over half the campaign’s volunteers. No other organization in New York City can provide as large or as skilled an army of volunteers over the course of a campaign—or during a lengthy recount process.

The Working Families Party (WFP) saved the day. The Cabán campaign was operating on a shoestring budget until the WFP endorsement in late March. The WFP paid for key campaign staff members and some paid canvassers, as well as reams of palm cards and digital advertising. (Ocasio’s endorsement in May also brought in lots of money.) The WFP also contributed strategic insights gained from 20 years of experience in New York City elections.

The closer ties forged between DSA and the WFP during this campaign could become transformative for New York politics.

The Cabán campaign extended the progressive insurgency from its Western Queens stronghold. As expected, the margin of victory was largest in Astoria, Long Island City, Sunnyside and Jackson Heights: where Ocasio did best last year and where the fight against Amazon was centered. But Cabán also won big in Ridgewood and by narrower margins in some precincts in College Point, Flushing, Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, Jamaica, Hollis, South Ozone Park, the Rockaways, and Southeast Queens. Even parts of Glendale and Middle Village, typically seen as conservative, went for Cabán (map). Both DSA and the broader progressive movement must build on this extension.

The results were in line with the campaign field strategy–but broader. Soon after endorsing Cabán, DSA’s electoral working group decided to focus its field effort on areas where most Queens DSA members live (Western Queens and Ridgewood) plus other areas where Bernie Sanders did well in 2016 (along the E train line out to Jamaica). In early April, the campaign adopted this approach, although it didn’t include vote-rich Southeast Queens, where the majority of the residents are black. This was a hard choice that seemed logical in a seven-person race, in which two of the three well-funded candidates (Katz and Councilmember Rory Lancman) had sewn up endorsements from Southeast Queens’ black churches and Democratic clubs before Cabán entered the race. As the campaign gained momentum and funding in May and June, the field operation expanded south to South Ozone Park, South Richmond Hill, Southeast Queens, and north to Flushing, College Point and Bayside. Endorsing organizations and neighborhood leaders brought Cabán to their churches, mosques, and parent associations, and called friends and family in their own languages.

The Cabán campaign may have overestimated the machine’s hold on Southeast Queens. As someone who spent a week going door to door in mid-June in the Southeast Queens neighborhoods of Springfield Gardens, Laurelton, and Rosedale, I can attest that the people I met there were highly receptive to Cabán’s message, particularly young people. A few cited Ocasio’s endorsement. Some mentioned hearing of Cabán on social media. Other canvassers had similar experiences.

The Cabán campaign was far more diverse than generally acknowledged—and not diverse enough. The 1,000 people packing the LaBoom nightclub in Woodside on election night included large numbers of Latin Americans, South and East Asian Americans, and white people; African Americans were underrepresented, though not a tiny minority. This mix aligns with the campaign’s strong performance in areas with large Latinx, Asian and white populations, and weaker performance in largely black parts of Southeast Queens and some Housing Authority buildings.

Long-term population shifts made the progressive movement’s growth possible, and contributed to the machine’s weakness. Downwardly mobile, mostly white young professionals in Astoria and Ridgewood, residents of new luxury towers in Long Island City, and Latin and Asian immigrants across the County have replaced much of the white working class, which traditionally supported the machine; Queens is now only 25% white. The newer populations don’t feel well-represented. In contrast, the more stable black community has had a piece of the power structure for decades.

In an election won by a narrow margin, any one of many factors can be called decisive. It’s possible that if the campaign had done more, sooner, in Southeast Queens or won a few more key endorsements, Cabán would have won by a wider margin on primary day, allowing her to maintain her win after the absentee ballots were counted—without a recount and lawsuit. It’s also possible Cabán would have won decisively if she had raised more money sooner or had simply had more time. When Cabán declared her candidacy in January, the primary was scheduled for September. Shortly after, the state legislature moved the primary to the last Tuesday in June to consolidate the dates of federal and state elections. If the legislature had made the shift effective in 2020, like some other election reforms adopted this year, the campaign would have another 10 weeks to extend its reach.

New York’s voting system sucks. The persnickety rules applied to nominating petitions as well as affidavit ballots were designed to disempower voters and challengers to the Democratic machine. While these rules have been loosened in court rulings and recent legislation, there’s much more work to be done.

We should all be proud of this vigorous, grassroots campaign and deserve a breather before resuming the fight. We have to think collectively about our mistakes and successes, and figure out our next steps in the battle to end mass incarceration and to expand the progressive and socialist insurgency, Incumbent elected officials in Queens and across New York City can no longer take re-election for granted.