By Ben D

I can’t think of a more cringeworthy phrase than “real music.” After a few decades on this planet, I’ve come to accept it as a prelude to the worst sorts of diatribes on the current state of music. Upon hearing those two words, I unconsciously prepare myself for what is likely to be yet another hot take on why “Rap isn’t music” or how “Dylan is the greatest living poet.”

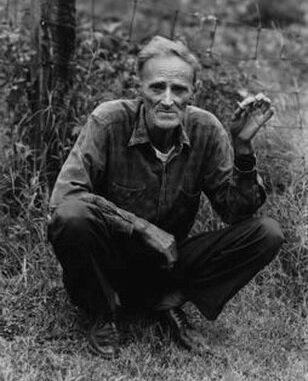

So it was admittedly a bit horrifying when, after hearing the music of Nimrod Workman for the first time, my first thought was: “this is real music.”

I first discovered the Appalachian folk singer through some work I did with the Association of Cultural Equity, which maintains ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax’s folk and traditional music archive. While there, I came across ethnographic footage of Workman on his porch, well into his eighties, beginning a song in a raspy voice:

“42 Years is a mighty long time

To labor and toil in that coal mine. . .”

Workman was born in Kentucky in 1895, lived to be 99 years old, and labored, fought, and sung through some of the most tumultuous decades of the U.S. labor movement. He first learned music at church, and refined his singing while on break from the coal mines, where he worked since the age of 14.

Around 1912, Workman became a union organizer along the West Virginia-Kentucky border, shortly after labor activist and IWW co-founder Mary Harris “Mother” Jones arrived to help create the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA).

In the early 20th century, being a union activist often meant risking one’s life. In 1912, immigrant textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts were beaten, shot, and bayoneted while pursuing the “Bread and Roses” strike in protest of pay cuts. In 1914, the Colorado National Guard, under the behest of the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, fired machine guns upon a camp of striking workers, murdering 21 people, including children.

In the Appalachians, unionized coal miners were regularly engaged in armed confrontations with “detectives” from the Baldwin-Felts Agency who were hired by coal companies to intimidate labor activists. As Workman recalls in the liner notes to his 1978 album Mother Jones’ Will, “There were a lot of people killed back then. They’d bar a union man from going to the store, and a lot of times we wouldn’t have anything to eat. The thugs killed one union man, tied his neck to the back of a truck and drug him up and down Tug River.”

In 1921, Baldwin-Felts detectives shot and killed Sid Hatfield, the sheriff of Matawan, West Virginia who supported the unionization effort. In response, Workman and others joined what became the Battle of Blair Mountain, an armed standoff between 10,000 armed coal miners and 3,000 strikebreakers.

In “Mother Jones’ Will,” Workman recounts his experience at Blair Mountain, focusing less on the standoff itself and more the heinous methods the Baldwin-Felts agents employed against coal miners:

“Well I’m goin’ to that Hart’s Creek Mountain,

Goin’ back to old Blair Mountain Hill

I’m goin’ to fight for the Union,

‘Cause I know it’s Mother Jones’ Will

Yes I know it’s Mother Jones’ Will

Well, our children were laying in the tents

They were laying upon the quilts

While the thugs were a-rambling through their tents

Pouring kerosene in their milk

Pouring kerosene in their milk.”

The standoff at Blair Mountain ended only after the Federal Government intervened, on the side of the the coal companies. The event became a setback for union organizing, and Workman returned to the mines. He lived in decrepit company housing, had to purchase his own tools to mine coal, and was paid meagerly in scrips–money that was only valid at stores owned by the coal company.

In the 1930s, Workman met union leader John L. Lewis, and again renewed his efforts unionizing mine workers. He helped with unionization efforts and strikes across Kentucky and West Virginia, and under the more sympathetic presidency of FDR, these efforts proved successful and greatly strengthened the UMWA.

After 42 years mining coal, Workman’s health faltered, and in 1952, he retired. Despite clear evidence of black lung disease, the company-employed doctor refused to acknowledge his ailments were mine-related, preventing him from receiving any compensation. Workman also struggled to receive a pension, and was only able to procure public funds to aid sufferers black lung in 1971.

After leaving the mines, Workman began a new career as a folk singer. At 79 years old, he recorded his first album, 1974’s Passing Thru the Garden, with his daughter Phyllis Boyens. His second album, Mother Jones’ Will, was released in 1978. In 1998, Drag City released I Want to Go Where Things Are Beautiful, a posthumous compilation of songs recorded by musician and folklorist Mike Seeger. Workman’s singing has also been featured in films, most notably Michael Apted’s Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter and Barabara Kopple’s documentary Harlan County USA, which follows a labor strike in Harlan County, Kentucky. Workman continued to sing in festivals across the country well into his 90s.

Collectively, Workman’s recordings are a testament to the particular time and place in which he lived. Each album contains an assortment of spirituals, blues and Anglo-Saxon ballads carried over from the British Isles to Appalachia—mostly sung a capella by Workman, but at times accompanied by members of his family.

His original songs, such as the aforementioned “42 Years” and “Mother Jones’ Will,” as well as “Coal Black Mining Blues” and “Black Lung Song,” are important contributions to this historically American repertoire, and help illuminate the perspectives of the otherwise forgotten workers who have been and continue to be exploited by the fossil fuel industry. Often autobiographical, Workman’s compositions poetically detail the everyday struggles and sorrows of the Appalachian working class, while maintaining an undeniable sense of the spiritual and, perhaps remarkably, the humourous. As Workman concludes in the “Black Lung Song,” for instance:

“When I get up in heaven

Gonna hug St Peter’s neck

When he tells old Paul and Silas

‘Give Nim his black lung check.’”

Beyond being an important historical contribution to American labor history, however, Nimrod Workman’s songs serve to illuminate a relationship between music and capitalism that may be too often neglected. Today, conversations about music seem almost inextricably bound to their commodity form: the album, the video, the tour. In this context, it’s worth remembering that decades before Nimrod Workman’s songs were ever marketed as records, he was singing them to fellow miners and to his family. Indeed, listening to Nimrod Workman reminds me of something the exploited classes in America have known for centuries: the truer purpose of music is found in collectively finding light in what is otherwise a very dark existence.

Nimrod Workman was the subject of a documentary, Nimrod Workman: To Fit My Own Category, available for viewing through Appalshop. Workman’s first album, Passing Thru the Garden, is also available through Appalshop. The posthumous album I Want To Go Where Things Are Beautiful is available on the Drag City website. For educators, a lesson plan is available here that uses Workman’s music as an entry point into U.S. labor History in the early 20th century (full disclosure: the author created this lesson plan.)